- Home

- Der Nogard

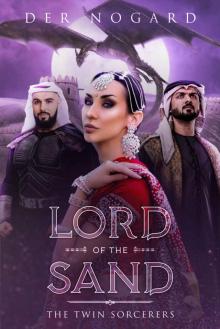

The Twin Sorcerers

The Twin Sorcerers Read online

Part 1: The Twin Sorcerers

Lord of the Sand:

A Dark Fantasy Reverse Harem Story

By

Der Nogard

© Copyright 2019 by Der Nogard - All rights reserved.

This is a legally binding declaration that is considered both valid and fair by both the Committee of Publishers Association and the American Bar Association and should be considered as legally binding within the United States.

The reproduction, transmission, and duplication of any of the content found herein, including any specific or extended information will be done as an illegal act regardless of the end form the information ultimately takes. This includes copied versions of the work both physical, digital and audio unless express consent of the Publisher is provided beforehand. Any additional rights reserved.

Finally, any of the content found within is ultimately intended for entertainment purposes and should be thought of and acted on as such.

Thanks again for choosing this book, make sure to leave a short review on Amazon if you enjoy it, I’d really love to hear your thoughts.

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Prologue

Dost awoke to find that he sat in the palm of a giant hand. This hand drew near a face, pulling Dost closer to it. It was the bearded face of his father. This face was lined with cracks of wisdom about the eyes, the brow covered by the bottoms of the turban folds. “There is no joy,” said Father. “No joy.”

Dost glanced at his father and his eyes were like planets, orbiting in a sad and unfamiliar way. The child knew that one day these orbs would cast no more light, just as suns must die, ending the sustenance of all that rely upon the sun’s shadow.

Father brought his hand low down to the ground and Dost climbed down the fingers to reach the ragged earth. This was an arid land, and the soil was thin like the soup of peasants. But the persimmon trees sprouted fruit, and in the spring the wadi was flooded with water, creating a plain upon which the horses might gaze.

But there was no joy.

Father removed the kujala from the heavy chain about his neck and placed the curved weapon upon the needy grass. The single feather that hung from his turban blew in the wind. “Once I was a child,” said Father, “and I saw the world through new eyes. But you shall never see the world through new eyes.”

Father turned way and asked a deputy to bring a horse. The horse was black and had a hungry look, like it was ready to lead its master to war. Its coat was brilliant and blinding, and the horse neighed like a crack of thunder. Dost ran toward the horse, knowing that his father was to go away, but he was too small: his little legs seemed to draw him farther away rather than bring him nearer. Father mounted his horse and took the whip that was handed to him. “Yah!” he cried and he whipped the horse to spur it on. Dost ran toward the man that drew away from him. But little boy that he was, he stumbled and crashed on the ground.

There was the familiar cry of thunder and he awoke. He felt the moisture as it formed a line down the cleft of his chest, but it did not come from sweat. There was a hole in the roof of the tent and the rain had been coming in all night.

A man clanged two blades together to announce that he was entering the tent. “Azag-al-Walaq,” said the man, and he bowed. “I came to bring you drink,” and the turbaned man approached the couch upon which the warrior had been resting. The warrior threw his legs over the side and heaved a deep sigh. As the new arrival reached out a hand, the warrior smacked it away, sending the flask flying to the other end of the tent.

“I will not drink,” said the man. “There is a hole in this tent. I might have died of cold if I had slept the night through.”

“Forgive me, my lord,” said the guard.

“Is Shaibani awake?”

“Yes, my lord.”

The warrior awoke and threw a fur-lined robe over his shoulders. “Take me to him,” he said.

“You are leaving, aren’t you,” Waqas Shaibani said as the warlord entered.

“I must make my own way,” said the warlord. “A man must eventually go off on his own, mustn’t he?”

“You have always been going off on your own,” Shaibani said. “Besides, that is not why you are leaving.”

The older man indicated with a hand that the younger warrior should have a seat on a couch adjacent to his bed. “As you know, it was always my intention that you would marry my daughter, Darejan. You might marry her today before you leave. I should like her to remain with me for a few years as she is the comfort of my old age, but after two or three years you may return and take her wherever you will.”

“That is not my wish.”

“But it is mine.”

The young warlord sighed. “I have already told you that I mean to go. I do not understand you at all.”

“But I understand you very well.”

The warlord stood and cast a hard look at his elder. “You imagine that you do,” said the young man with the long black hair, smiling finally. “You think you do, but you do not.”

The elder man stood up and approached the younger. He found no joy in the young man’s eyes, seeing instead only a deep, irrepressible anger. “You seek your fortune somewhere else,” said the elder man, suddenly afraid. He would watch as the young warlord set free the long locks of his youth, casting the hair to the ground and burning. He watched as he cast aside his black armor, giving this piece to this man and this to the other. It was with some confusion that he saw the young man remove even the characteristic mail from his horse. This would be melted down to make a new suit of mail for one of the recruits that constantly flocked to this rebel army that terrorized the land.

The elder warlord saw the many veiled woman that had come to him as gifts from frightened lords from all around the steppe. Their cloistered lives perhaps were freer here, living on this grassland that must always cast a libertine wind. He watched the women and knew that it had all been worth it. Though he had clawed for life from the days of his youth, though he had lived as the scorpion in the desert, he had known joy.

Chapter One

It was the sea foam that washed the lady onto shores of a city on a Great Northern Sea. The sea foam has no sense of time, at least it does not understand it the same way that we do, so it did not know to wait until the morning sun had risen to wash the nude maid out of the sea arms into the cruel land of men. The sun burnished her skin making her seem to glimmer when the morning gust hit her. She was of a singular beauty.

Her hair was like wind rolling across the steppe and in her eyes were ships lost at sea. Upon her brow was time itself, but a time so long and lazy that it regarded the world with confusion at its cares. The lady had a sharp widow’s peak in her black hair, a mark which was, in this time of the Sons of Yunus, regarded as pleasant and unusual.

When the residents of the city found her, the lady was shivering and wearing seaweed for clothes. She had not seen the need for them, for clothes that is, but the kelp, almost as if by a decided will, had come to drape and cling to her as she approached the strange onlookers gathered to stare. This was a land of modest people, where the women were veiled, the high-born women never permitted to leave the harem. When the girls were married, they were paraded in front of their husbands arrayed in seven different dresses, one after the other, showing their mate the beauty of the woman they were to wed. And when the moment came, when the marriage vows were spoken and the union was solemnized, the veil was dropped.

So t

his unveiled woman was regarded with fear and confusion. The people massed around her and carried her back to the sultan, who received her at the threshold of his hall of elephantine. Not knowing what to make of her, as she would not speak, the sovereign gave her to his son, Prince Ghazan, who resembled his father as much as a porpoise resembles a desert bear.

Prince Ghazan regarded the girl as midnight regards the day. He knew instantly that she was not of the Banu Yunus, if the kelp dress and lack of a veil did not give her away. She did not seem to mind the cold wind that was just then enveloping the desert. You see, the city of Maler lay along a northern desert, the northernmost desert in the world. It lay north of the duchies of Randalkand, where the dukes fought each other like wyms, and north even of the steppes of Talgud, where the people were all either nomads or pirates, selling hordes of slaves either by sea or by land.

“I know you are not of this land and I will not ask what your land is,” the prince told the lady.

The prince had come to see the lady every day, sneaking into the zenanah, and she had never once spoken. Weeks had passed all in the same fashion. The sultan’s court would gather, all the Wazirs, Emirs, Chamberlains, and Nabobs, receiving emissary from this foreign king or the other, and the main would stand by the other foreign maidens, not saying a word. After supper, the prince would scale the wall into the zenanah and attempt to enchant the lady with this fictitious tale or that. He told her of the great beauty of the Queen of Vani, who loved in an island on the Southern Sea. He told her about men that could change into wolves. He told her about the dragons who lived below the steppes or in mountains, waiting for the proper moment to strike, but she never said a word.

“I suppose all lands are the same,” said the prince on this day. “A man told me something like that once. People are the same everywhere.”

The lady gazed at the prince, at his sad and sensitive green eyes, and she suddenly had the urge to speak. “I,” she began, finding words difficult to grasp, time-consuming, and altogether meaningless. “I would cast aside this kelp dress,” she said.

“Yes,” said the prince, smiling suddenly. “Of course.” He looked about this great open chamber of the zenanah, at its expensive hangings and its cushions of gold and silver thread. “Certainly a maid of your loveliness deserves something more fitting than this cheap stuff of the sea. You are as the moon whose fingertips touch the desert and cast all into grateful slumber. Or the sea-edge whose waves massage the coast to the heights of ecstasy. You are like a bountiful land unplagued by wyms and their…”

“Do you always have so many words?” asked the lady.

“Why, no,” said Prince Ghazan, looking around the zenanah again. He was not meant to be there, as he knew. He was an adult prince. Only the sultan and his children were allowed in the zenanah, and once the male children reached maturity, at about age 15, when their top lock was shorn, then they too had to leave the sultan’s pleasure place. The sultan had many treasure-chambers, but this was the most prized of them all. In the eyes of the sultan, boys of this age were nothing more than other men in the palace, even if they were his sons. The only men allowed into the harem were the eunuchs, and the palace of the sultan teemed with these men who occupied every post from scribe to messenger, guard, cook, and manservant.

“That man,” said the lady. ”Why does he gaze at me so?”

The lady had just finished having her hair perfumed with the scent of the desert lotus and her body massaged with willow water. These were unfamiliar scents and sensations and she felt both relaxed and hyper-alert.

“Because you are beautiful,” said Prince Ghazan, glancing down timidly. “Don’t you know that? You are the most beautiful maid ever to have touched ground in Maler.”

“Where?” asked the lady. “What did you say? What land is this?”

“Maler, the mightiest of the twin kingdoms of Banu Yunus. Built atop the Tell-Babi. Beneath the present city, in the bones of the previous one, I am certain that there was a love temple where you would have been the high priestess. They would have scented your hair with dragon tears and arrayed your neck in collars of young pearls. You are like a pearl without price, don’t you know? There are not even girls as lovely as you in the slave mart, where there are ten thousand girls waiting to be sold this very moment. The most beautiful of them is not worth the twisted, black hair on your pinky toe.”

“The what?” asked the lady. “I have no need for your flowery words. They are as the sugar cake; sweet to the taste, but soon faded to memory.”

“So you like cake, milady,” the prince wondered. “I am at your service. I am sure that I can find a cake seller to meet your desire. The town teems with them. What sort of cake do you fancy? I suppose you do not mean the humble street cake, sold even to the wretched thief or wanderer. You mean I cake made especially for you. I completely understand. I shall have to find my way out of the zenanah and into the city, perhaps jump over the wall, but I shall return this evening. The wall is perhaps the height of twenty men, but if I survive the fall I shall be glad to return to you. With your sugar cake, of course.”

“That is not what I meant.”

“Yes, I believe I understood your meaning.”

“Alas, you do not.”

“Perhaps you might enlighten me, milady,” said the prince. As my shoulder awaits the touch of your fingers, so do my ears await the pleasure of your words.”

“I,” began the maid. “You know, I find your words rather tiring. Where I hail from, we have no use for words that have no meaning or for dissimilation. I do not understand flattery at all.”

“You said we, milady,” said Ghazan. “Who are your people? I suppose you were referring to them when you spoke those words. Might I ask what is your land and who are your people?”

“I do not know,” said the lady.

“Oh, it does not matter,” said the prince. He wished the chief eunuch would leave so that he might have a moment alone with the lady. Everything he said, even the thoughts that passed through his mind, would be reported to the sultan, his father. His sultan used eunuchs as spies, plying the land for youths that had the art of telepathy. These would be made into eunuchs. If the parents would not sell them, they would be kidnapped so that they might form part of the sultan’s veritable army of eunuchs. Of course, Ghazan did not know if there was any truth to those words, as he himself was always kept under surveillance and never permitted to speak to anyone that was worth speaking to, but this was what was said in town. Ghazan knew his father to be sensitive, if not somewhat prone to outbursts of passion. His eyes told the story. One moment stern, the next stormy. Finally, they would soften. Ghazan did not believe his father the sort who would engage in the trade of forcibly making men into eunuchs. He could not believe that anyone would behave thusly. It would not be until he himself became sultan that he would come to see the world as it was, not as it was fashioned in the elephantine tower in which he resided. The cruelties that he occasionally saw, a slave who was whipped for raising their eyes to gaze at a member of the royal family, the poor beggar children who opened their hand for coin or food outside the palace window, the spahbads who were executed for failing in a campaign, these harsh realities paled in comparison to the cruelties that passed every day in the world. These were cruelties that Ghazan did not know then, but which he would soon learn.

“I suppose you are right,” said the prince, leading the lady down a hall whose walkway was inlaid with dragonwood. Even here, in the innermost halls of the zenanah, they were followed by eunuchs. “Different tongues for different people. I suppose the tongue expresses the character of those who speak it.”

“Your father,” said the lady, seeming to have great difficulty with the words. “Will your father truly execute you for entering the… What did you call it?”

“The zenanah,” said the prince.

“Yes, the zenanah,” said the lady. “He will have your head for it? You were telling me something like that before. Your father�

��s spies will report it back to him?”

“Oh, yes,” said Prince Ghazan. “My father will learn of it, have no doubt about that. But he will not have my head, at least I hope he will not. I am his only son after all. He would have to sire another one and he’s too old for that, you understand.”

The lady gazed around her, at the intricate silverwork ceiling, the painted woodwork of the windows, and the golden fountains in the courtyards, and it was like flattery in another form. The entire kingdom would seem like this, when she would finally leave the harem when the priest Dir-en-Shad came to the land. Even the desert, with its stark yellows and whites, still formed a beautiful scene: a place that bred warriors just as easily as it bred simple men and women. It was all a form of flattery, especially here in the palace, where wealth seemed to be drawn from the varied lands of the world. The variegated columns of the throne hall, the multicolored tiles that lined the insides of the pools: these were like a jester playing some sort of grand joke. The lady found that she yearned for the mother-of-pearl walkways of the sea, the opal halls of the Eastern Rim, beauties that only the sea and the earth, in their honest way, could provide.

“Flattery has a purpose,” said the prince. “The first thing a man learns is how to flatter a beautiful woman. Please do forgive me if my flattery ill-suited you. I only said those things because I love you, and how else can one express a sentiment as strange and unsteady as love but by flattery?”

“Me?” asked the maid. “Love me? How can you, prince, love me? You do not know me.”

“Needest a man know the sun to love its light?” asked the prince. “I know what I feel when I see you and that is enough. I hope that it shall be all the sustenance that you require too, milady. Please, let us talk no more of this. My father receives Princess Rusudan in the throne hall. Come, let us go to her. She will tell us what the future has in store.”

The Twin Sorcerers

The Twin Sorcerers